Super-

Local

Luc van Hoeckel

Luc van Hoeckel designs solutions for the 90% of the world's population without access to decent basic facilities. For example, he made hospital beds in Malawi and came up with a solution for pollution from tourism in Nepal. By working with local materials and setting up production locally, goods can be easily manufactured and repaired. This makes products much more sustainable and creates jobs in places where there is often high unemployment.

Most products in the world are designed for about 10% of the world's population, according to Cynthia Smith, author of 'Design for the Other 90%’. Most of the global population therefore has little or no access to products and services that we take for granted. The manufacturing industry in developing countries often produces low-quality products, and imported products are prohibitively expensive. Donated goods can end up unused in landfill because they do not work as needed or cannot be repaired locally.

We spoke to Luc about design in developing countries and how he adapts his approach according to local demand, habits, and taste, which can be very different from his own.

Photography: Anouk Moerman

Film: Blickfänger

Hi Luc, tell us: what drives you, what is your passion and where does it come from?

Making something, designing something, is almost like meditation for me. Working with materials, feeling different textures, the roar of production machines: the whole creative process makes me very happy. In high school there was a teacher who believed in me and encouraged me to take this further. Thanks to him I was able to attend Sint Lucas College, my first education in design. It was there that I knew for sure: this is it! I wanted to be the next big thing in design. That’s why I continued my education at the Design Academy in Eindhoven. You were on your way to becoming a rockstar designer, what did you want to create in the world?

At the Design Academy I grew as a person and also gained a new perspective on the world around me. In my third year I realized; the world is on fire, while I’m designing new tables and chairs. I came across a book: ‘Design for the Other 90%’. The book explains that traditional designers develop products and services for 10% of the population, the group that can afford design.

What can we design for 90% of the people who also want access to well-designed products and services, who need it much more than we do due to poverty or other challenging living conditions? I found that thought so inspiring.

Through the Academy we were able to do a project in Nepal for a pharmaceutical company. After six weeks of research in rural areas, we discovered that many patients from rural areas didn’t know how to correctly take prescription medication and couldn’t read the instruction leaflets. By placing illustrations and infographics on medication packaging, we could show them how to best take the medication. This is where I learnt that as designers we can commit ourselves to making a real difference for people who need it. My classmate Pim van Baarsen and I started Super Local in 2012.

Traditional designers develop products and services for 10% of the population.

You say you want to make a difference for the 90% of people on earth who need it most. Can you explain this, what is your approach?

We work in lots of different situations. We have designed products for a hospital in Africa, and also spent time on a landfill to come up with a new waste processing service in Nepal. Our projects vary, but our approach is always the same. This is based on the Human Centered Design method, which means that the needs of the end user are central.

That means that we don’t start by pitching ideas, but first thoroughly research the problem to properly map out the sometimes complex context. We don’t think the world needs superheroes, but good listeners. That’s our role.

Our process consists of three things. First, we investigate the demands, needs, preferences and wishes of the target group. Secondly, we consider what materials are available locally, but also what knowledge and production techniques are available. And finally, we establish what kind of business model will make the solution financially feasible. Another important goal is to generate as much local employment as possible with every project.

Instead of a rockstar designer or a superhero, you became a Human Centered Designer. What does that actually mean?

The Human Centered Design method is a very organic process. In fact the most important thing is building egalitarian relationships with the people we work with. This peer relationship is important to fully understand the real problem. That’s why we take plenty of time to conduct thorough local research and invite conversation by putting people at ease.

The exact way to go about this varies. We use different interview techniques. We also like to spend time with the local community, to observe their daily lives and reality. Sometimes we work with a craftsman all day to learn a technique ourselves. To break through cultural barriers and also engage with people who are shy or timid, we sometimes work with card sets where you can point to things.

It's not a fast process. Investing in personal relationships and getting to know each other is key to ultimately create a good design.

And then after all that research you come up with a solution. Can you give us an example of the kind of products you design?

For example, we have a project in Nepal where we collect plastic waste in the Himalayas and process that into new products in a plastic recycling workshop set up for that purpose. The entire process from collecting the waste in the mountains to selling the products in a store is run by the local population.

The initial request from our client was to make products for the local population. We wanted that too, but our research showed that revenue model was unprofitable. So we pivited and proposed producing products for tourists made from the same plastic waste they produce during their Himalayan vacation. This meant we could set up the recycling plant. The next step is to expand into making products that can be used locally.

Another example is a hospital project in Malawi where we were asked to develop new hospital products. The problem was that most of the inventory of Malawian hospitals were donations from America or Europe, but these products did not meet local needs. For example, power was not always available to raise or lower the electriconically-controlled beds.

We developed the products together with craftsmen in a metal workshop in Malawi.

And repairs couldn’t happen locally because spare parts and specialist knowledge were lacking. To fully understand this problem, we spent weeks shadowing doctors, midwives and patients to see how they work and how the products were used. Observing the hospitals in use helped us to understood why many of the beds sagged in the middle. In Malawi it is very normal that when a patient is in hospital, the whole family comes to visit and many sit on the bed together. These are things that you could never find out thourgh conversation, you just have to see it for yourself.

Together with the staff of several large and smaller hospitals, we have designed a complete range of furniture, including hospital beds, operating stools, operating tables and trolleys, partitions, infusion bag stands, bed tables and washing trolleys. All made to be low-tech, affordable, and locally produced and repaired.

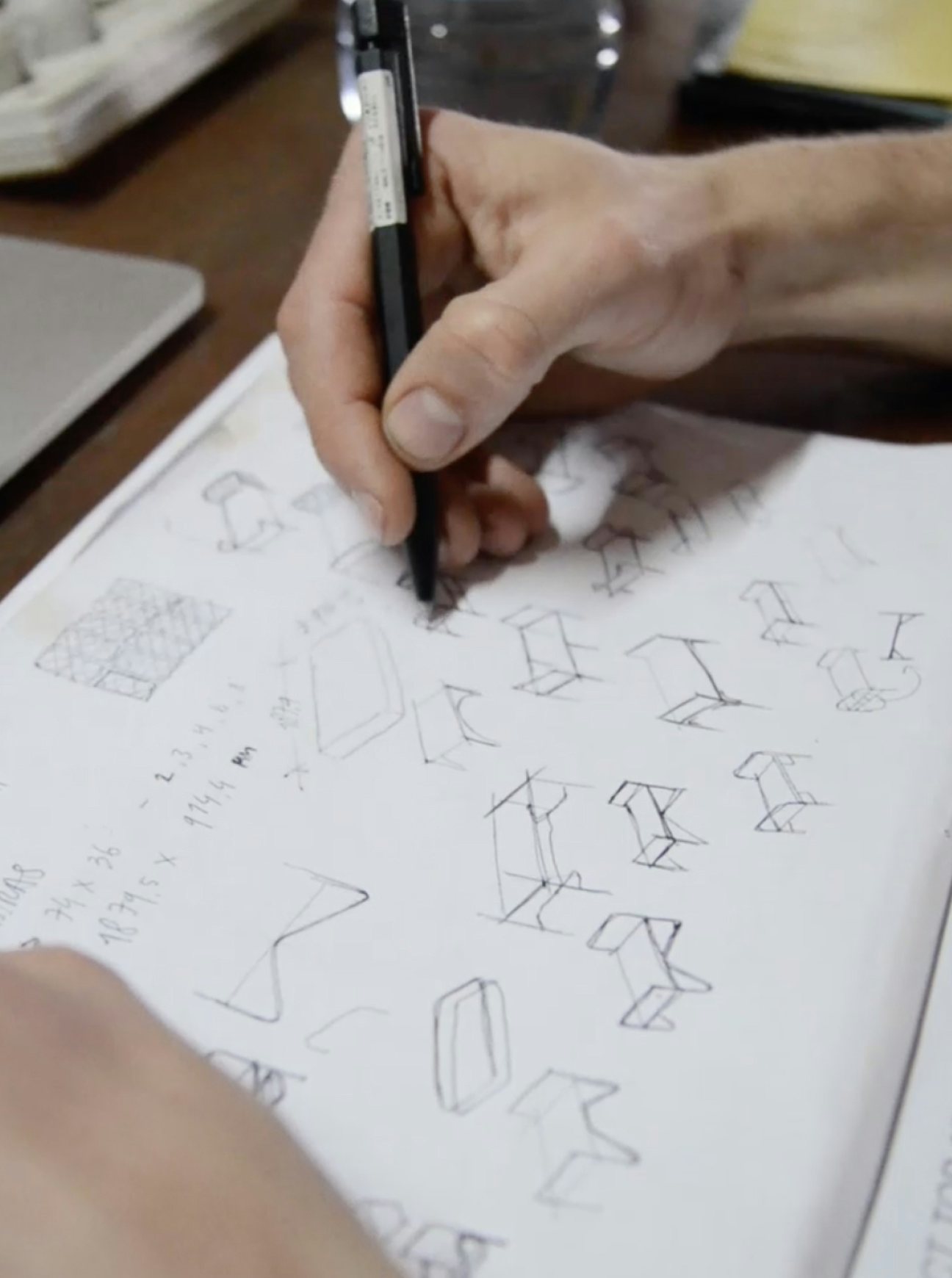

One of the best things about this project is that we have been able to create a lot of local employment. We developed the products together with craftsmen in a metal workshop in Malawi. We also taught the craftsmen new techniques, such as mocking up technical drawings in a 3D computer program. Now we are no longer needed and they can develop and manufacture new products themselves.

We want to give waste value again and create a business model around it that has a local impact.

It sounds like you work with many different materials. How do you choose the materials you need, and what role does circularity play at Super Local?

Sustainability is key in our work, and solving a waste problem is often the place of departure for a project. It's such a bizarre idea that if a product is thrown in the trash, it loses its value. We want to give waste value again and create a business model around it that has a local impact.

Yet another example is a project we did in Zanzibar. A large part of the population on Zanzibar is Islamic and does not drink alcohol. But the tourists who come for the beautiful beaches do like to have a drink.

The result is a mountain of glass waste that has nowhere to go. We designed a series of products that can be manufactured from this waste stream. For example, we have come up with a way for tourists to take their own waste with them when they leave the island, packaged in an attractive product that they paid for.

The Himalaya project works in a similar way, where we use plastic waste left behind by mountain climbers. We turn the plastic waste into souvenirs they can purchase as a memento of their climb. We came up with the idea that they carry it down the mountain themselves, in order to set up a logistics system where tourists take ownership of the pollution problem. You may of course wonder whether making a souvenir is truly sustainable. But the impact we are creating is the tons of plastic waste that are recylced and processed locally. The souvenir is a means to achieve that goal.

Sustainable design is not an easy process and it’s certainly not easy to work in a developing country. What are the biggest dilemmas you face in your projects?

What we faced in the early days is that as a designer you have a certain preference about how a product should function or look. We have learned to let that go. Our work takes place in a completely different context. That also means a different perspective on what makes something beautiful. Our goal is to make a difference locally, and that can mean developing something we don't love, simply because the local population thinks it's fantastic. That's why it's so important to listen carefully and constantly ask for feedback throughout the design process.

What also makes our work challenging at times is that we have to work in quite extreme conditions. In developing countries, it can be extremely cold or ridiculously hot. We have slept on mats in straw huts and I’ve had malaria. This is all part of the adventure and results in many beautiful experiences and products. But the older you get, the more this takes out of you. I might be getting to the point where I want to be home more often. And of course, we feel uncomfortable flying so much in the current climate crisis. But to make local impact and recycle waste, I fly all over the world. So far the end justifies the means, but this is something I am pondering.

In the meantime, I have to keep Super Local going financially. I feel rich inside, but it’s not always easy to find partners with a similar vision who also have the budget available to set up a sustainable project. This studio is my fuel for life, but I also have to ensure that I can make a living from it.

Think twice before you design a new product.

Working for your target group is a financial challenge. How do you see the future of Super Local and what will it take to get there?

Right now I'm in the middle of something of a redesign of Super Local’s proposition. We have worked together all over the world for many years, but Pim has a young family and we mutually decided that from here on out I will continue the studio on my own. I'm taking a six month sabbatical to think about the future. After all those foreign adventures, I would also like to make more of an impact in the Netherlands. Especially around waste, because although things seems very well organised, there is still a lot to be improved.

I would prefer to focus on one problem, with a solution that I can scale up. Of course, this also involves some funding. These ideas are still in their infancy, so the Secrid Talent Podium with professional coaching came at just the right time!

To everyone who wants to support you, what message do you have for them?

I would say, yes - the problems in the world are big and complicated. My advice is to go talk to your neighbour, to an 'ordinary' local person. Do your research and listen carefully. You can always make a difference. But I really want to pass on a message to my fellow designers. We don’t need more tables and chairs. So, think twice before you design a new product. Consider the impact it will have today, and for generations to come.

Instagram: @superlocal

Historias cortas

Secrid Talent Podium - Sumo Baby

Luisa Kahlfeldt markets a high-performance diaper that reduces a baby's diaper use from about 5,000 to 25 diapers.

Secrid Talent Podium - ClimaFibre

Sunflowers can help to reduce our dependence and the environmental damage of cotton in the fashion industry.

Secrid Talent Podium - Fungi Force

Entrepreneur Frans van Rooijen and scientist Dr. Michael Sailer are launching a varnish made from natural raw materials.

Secrid Talent Podium - Vorkoster

To combat food waste, Kimia Amir-Moazmi is working on a product that allows consumers to see for themselves whether food is still safe to eat.

Secrid Talent Podium - Solarix

Solarix designs and produces aesthetic solar panels as façade cladding.

Secrid Talent Podium - Claybens

Emy Bensdorp is developing a technique to transform clay soil contaminated by PFAS into 100% clean bricks.